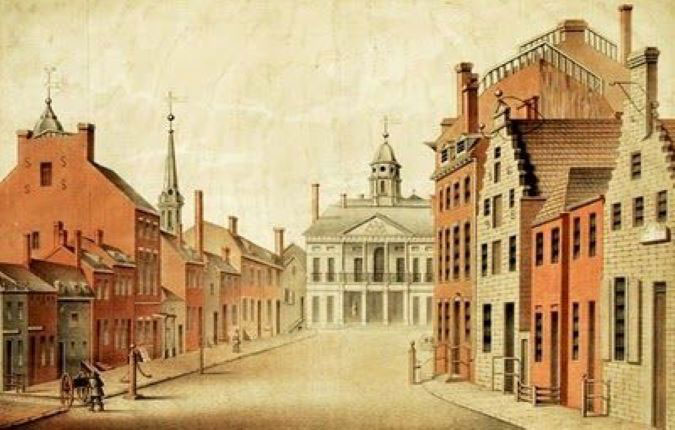

Rachel Hoping Robinson was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on July 12, 1785, to Abraham and Rosanna McGowan Robinson. Rachel came from a small, Quaker family. She was brought up in a highly civilized city in the British Empire, and her upbringing was refined and wealthy, and she was well-educated. The Robinsons owned and operated two boarding houses.

LINK TO ENDNOTE: What is a Quaker?

In the summer of 1793, a yellow-fever epidemic struck Philadelphia, capital of the United States from 1790 to 1800, and its largest city. It took the life of Abraham Robinson.

LINK TO ENDNOTE: What is yellow fever?

Several years later, about 1800, John Johnston became a border with the Robinsons. He moved to Philadelphia to take a job in the War Department. Rosanna Robinson had a daughter, Rachel, 10 years younger than John.

While John was living with the Robinsons, he fell in love with Rachel. John asked for her mother's consent to marry, but was refused. On July 12, 1802, 27-year-old John, an Episcopalian, and 17-year-old Rachel, a Quaker, eloped to Lancaster, Pennsylvania. The Rev. Gottfried Muhlenberg, a Lutheran minister, married them in a German ceremony on July 15, 1802.

The honeymoon was a nearly 600-mile horseback journey to John's new post as the factor (store-keeper) at the Fort Wayne Indian Agency in the Indiana Territory. John's federal appointment as factor came as a result of his high standing in the War Department.

The arrival of the young couple to Fort Wayne, still very much a frontier outpost, must have been a shock to the young Rachel, who had grown up in the sophisticated environment of Philadelphia. Rachel now had to manage a home and raise children.

During his time at Fort Wayne, John became familiar and knowledgeable with the customs of the Native Americans who came to conduct business. Rachel's Quaker background helped her husband better understand and value the various native cultures.

On September 6, 1804, John purchased land that would become his Upper Piqua farm in the northern part of the Miami Valley of Ohio. In 4 years he built a log barn and a two-story log cabin.

Rachel gave birth to four children, Stephen, Rebecca, Elizabeth, and Rosanna, at Fort Wayne. Rebecca died in 1807, age 2, of an unknown fever. As both John and Rachel contracted malaria, it is likely that Rebecca died from malaria. John and Rachel survived.

LINK TO ENDNOTE: What is malaria?

In 1809, John was appointed Indian Agent at Fort Wayne. The duties of the agent were much more political in nature whereas the factor tended to the business side. John served in this dual role until his resignation on June 30, 1811, citing ill health as a result of malaria.

Following John's resignation, he moved his family to become a "gentleman" farmer in northern Piqua. A fifth child, Juliana, was born in 1811, shortly after their arrival in Piqua.

A year later, in March, President James Madison appointed John to a new post as Indian Agent for the Shawnee in the newly created Piqua Indian Agency.

Rachel's life was tied closely to that of her husband. While John managed the Piqua Indian Agency, Rachel managed the farm and children. The Indian agency was located on the Johnston Farm, thus John and Rachel often worked together and supported each other.

On June 18, 1812, John's duties expanded with the American declaration of war against Great Britain. He was appointed colonel, and assigned as paymaster and quartermaster for General William Henry Harrison's Army of the Northwest. It was stationed on the Johnston farm and locally known as Camp Washington.

Between 1812 and 1815, the Johnstons built a two-story brick home in the Federal style; it was one of the grandest homes in the Upper Miami Valley. A new, larger home was necessary because of the growth of the Johnston family. Ten more children were born between 1813 and 1830. The children comprised ten girls and five boys, with all but one living to adulthood. This was remarkable as 46% of all children living in the United States in the early 1800s did not live to their fifth birthday.

LINK TO ENDNOTE: See the names and birthdates of the 15 Johnston children!

The Johnston family was growing and John's various duties often kept him away. Rachel oversaw the operations of the farm, along with John's mother, Elizabeth; she moved to Ohio about 1812, after the death of her husband. Elizabeth died on August 18, 1834, age 89, and was interred in the farm cemetery.

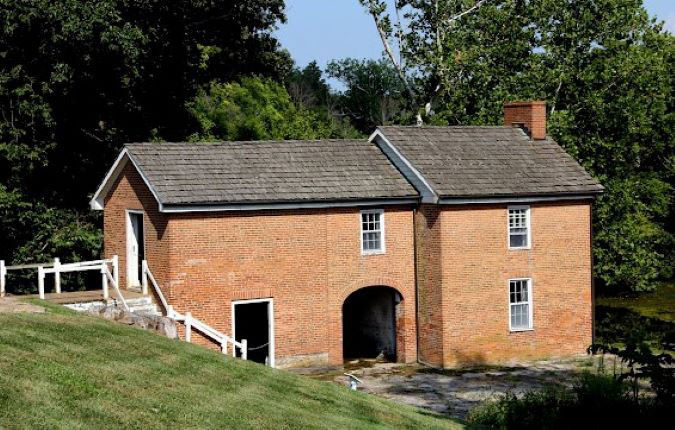

Rachael's tasks included supervising the farm and dairy, and assigning and managing her children's chores. Workspace on the upper floor of the springhouse was kept busy with the spinning and weaving of fabric for clothes and blankets.

Cooking was a day-long process and included baking bread and drying fruit. Visitors, including government officials, politicians, and Native-American chiefs, were frequent, thus, food always had to be ready to serve. Rachel and her daughters were often kept busy in the dairy and kitchen preparing food. As the older girls married and left the farm, Rachel obtained help from girls in town.

The Johnstons also made their own candles, clothes, and small household goods. This lifestyle was quite different from the one Rachel had known in Philadelphia.

John and Rachel were founding members of St. James Episcopal Church in Piqua in 1823. John served as a lay reader and led services until the first pastor, Rev. Gideon McMillen, arrived in 1825. Until 1828, services were held in a small, wooden schoolhouse erected near the Johnston cemetery.

Rachel served as a Sunday-school teacher, and was a founding member and president of the Piqua Bible Society, a post she held for 15 years.

LINK TO ENDNOTE: Read part of Rachel's address to the Piqua Bible Society!

The Johnstons were also the founders of the first subscription-school in Miami County, forerunner of the public-school system. The building where church services were held on Sundays became the schoolhouse during the week. John and Rachel encouraged their children to obtain as much education as possible with no preference given to either the sons or the daughters.

Rachel died when she was 55 years old on July 24, 1840, following a brief illness; she was buried on the Johnston Farm. Following her death, John found it increasingly difficult to continue living on the Piqua farm, especially as most of his children left home to marry or enter military service.

LINK TO ENDNOTE: Read about the marriages and military service of the Johnston children!

John continued to live on the Piqua farm until 1848 when he moved to Cincinnati to live with his remaining single daughter, Margaret, and single sons, William and James. In 1849, a cholera epidemic struck Ohio. Over 4,000 people died in Cincinnati, representing 5% of its population. And over 300 people died in Dayton, representing 7% of its population. Margaret contracted cholera on June 21 and died the same day.

LINK TO ENDNOTE: Read about the cholera epidemic of 1849!

Following Margaret's death, John moved to Dayton to live at Rubicon Farm, home of his daughter, Juliana "Julia" Johnston Patterson, and her husband, Jefferson Patterson.

In December 1860, John and his son, James, travelled to Washington, DC, to press Congress for reimbursement of expenses incurred throughout his years as the Indian agent in Piqua. He was also there to lobby for a grandson, likely William Graham Jones, to be appointed to West Point. William was the first son of John and Rachel's eldest surviving daughter, Elizabeth Johnston Jones.

John Johnston died on February 18, 1861, in Washington, DC. He was buried at the Johnston Farm in Piqua next to Rachel.

ENDNOTE - What is a Quaker?

Formally known as the Religious Society of Friends, Quakers represent a Protestant Christian denomination founded by George Fox in mid-17th-Century England. It dissented from the established Church of England.

The Quakers generally believe that all people can encounter God directly, without the intervention of ministers or priests. They are usually pacifists, wear plain clothing, do not take oaths, and oppose slavery. Facing persecution from the Church of England, many Quakers migrated to North America shortly after their founding.

ENDNOTE - What is yellow fever?

Yellow fever is a virus typically spread by a certain type of mosquito common to tropical and subtropical locations. It is believed that the outbreak in Philadelphia in 1793 was brought by immigrants fleeing slave revolts on the French Caribbean Island of St. Domingue (now Haiti). Contributing to the situation was that Philadelphia experienced an extremely hot and humid summer in 1793. It is estimated that 10% of the population died; nearly 5,000 people.

ENDNOTE - What is malaria?

Malaria is a disease caused by a parasite. The parasite is typically passed by an infected mosquito through a bite to a human. While it is more common in tropical and subtropical environments, it can be present in any hot and humid environment that attracts mosquitos.

The symptoms of malaria include fever, headache, fatigue, and vomiting. As it worsens, it can cause jaundice (yellowing of the skin), seizures, coma, and death.

ENDNOTE - Who were the Johnston children?

John and Rachel Johnston had 15 children, 14 of whom lived to adulthood. They were:

ENDNOTE - Read part of Rachel's address to the Piqua Bible Society!

"...Let us be more and more devoted to this duty and let us, by labors of love, invite others to come with us, that we may do them good also; for the consolations of the Gospel are neither few nor small, and it is not among the least of its benefits that the soul employed in benefiting others for the sake of Christ, shall be more abundantly watered. To do good and to distribute, forget not, for with such sacrifices, God is well pleased. If thou hast much, give plentifully. If thou hast little, do thy diligence gladly to give of that little."

Conclusion from address to the Piqua Bible Society, St. James Church, Piqua on May 4, 1840 (Conover, 1902, pp. 92 — 93, citing Mrs. John Johnston).

ENDNOTE - Read about the marriages and military service of the Johnston children!

Marriages of the Johnston children:

Military service of the Johnston children:

(From Conover, 1902, p. 93, and pp. 102 — 103; and the National Archives and Records Administration)

ENDNOTE - Read about the cholera epidemic of 1849!

Cholera is a highly contagious bacterial disease present in contaminated food or water. Typically, the contamination is from the feces of an infected person. It is common in areas where there is a lack of sewage treatment and clean drinking water. Left untreated, cholera causes gastrointestinal symptoms, including severe vomiting and diarrhea. It can strike suddenly and result in death in less than a day.

In 1849, Dayton had a cholera epidemic that began in May and lasted through the summer. Typically, cholera is less active in the cold months of winter.

Burba (1931) suggests that the canal, with travelers from Cincinnati, brought cholera to Dayton in late May 1849. A cholera epidemic had begun in Cincinnati in early May. The recently opened canal made travel easy and convenient. Some of these travelers were on business while others were fleeing the epidemic in the larger city of Cincinnati for the less populous city of Dayton.

Complicating factors for Dayton were a lack of a sewage system, unpaved streets, no hospitals, no board of health, no quarantine laws, no effective drugs, no trained nurses, and few doctors. Several doctors formed a board of health on June 20, 1849. The board, however, had no regulatory power and could only make suggestions on how people should change their behavior to avoid contracting or spreading cholera.

By September 1849, the cholera epidemic disappeared in Dayton. However, the approximately 300 people who died during the epidemic may not be an accurate reflection of the total deaths in the Dayton area. While Dayton city deaths were regularly recorded, they did not include people who returned to their homes and farms in outlying areas, and died from cholera or spread it to family members and neighbors who subsequently died.

Burba, H. (1931, March 8). When the Cholera Plague Swept Dayton. Dayton Daily News. Retrieved March 26, 2022 from the World Wide Web: https://www.daytonhistorybooks.com/page/page/5895433.htm

Conover, C. R. (1902). Concerning the Forefathers: Being a Memoir, with Personal Narrative and Letters of Two Pioneers, Col Robert Patterson and Col John Johnston. New York: Winthrop Press.

Hurt, D. R. (1996). The Ohio Frontier: Crucible of the Old Northwest, 1720 — 1830. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Knepper, G. W, (1989). Ohio and its People.. Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press.

Smith, M. (2020, June). Pandemic Redux: Revisiting Cincinnati's 1849 Cholera in the Age of COVID-19. Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective.. Retrieved March 26, 2022 from the World Wide Web: https://origins.osu.edu/connecting-history/cincinnati-cholera-covid-19-revisited?language_content_entity=en

Do you have photos, books or other information that you believe may be pertinent to this website?

Are you interested in contributing to our organization?